The Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) of 1934 led many American Indian tribes to adopt formal constitutional texts to govern life on reservations. Over the following decade, dozens of tribes ratified their constitutions in hopes that they would start a new age of tribal self-governance. Given the opportunities for constitutional design subject to constrains, we develop a theory of constitutional choice on reservations. Tribal constitutions varied substantially in content and structure. We evaluate the constitutional choices tribes made regarding four areas: membership requirements, direct democracy, restrictions placed on officials, and protection of private property. Our theory yields several hypotheses that we test against data on 117 tribal constitutions, most of which were ratified in the aftermath of the IRA. The results provide evidence for the validity of our hypotheses.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Price includes VAT (France)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Our approach differs from that of some previous work on American Indian matters in the public choice literature, which emphasized the effect of rent-seeking on tribal economies, especially at the federal level (McChesney, 1990; Anderson, 2016).

Blood quantums have a peculiar status in American law. The Supreme Court has generally recognized their legality by framing them as legitimate political, rather than racial, instruments to advance the interests of tribal members. See for instance Morton v. Mancari, 417 S. Ct. 535 (U.S. 1974). However, more recently federal courts have questioned the ability of American Indian polities to use blood quantums to exclude individuals with historical links to a tribe from political participation. In particular, the courts struck down a provision of the Cherokee 2007 constitution denying the Cherokee Freedmen, the descendants of slaves owned by the tribe, the right to vote in tribal elections. See Cherokee Nation v. Raymond Nash et al., 267 F. Supp. 3d 86 (D.C. 2017). The issue of the relationship between blood quantums, tribal membership, and American Indian sovereignty was also discussed during oral arguments leading up to the recent Oklahoma v. Castro-Huerta, 42 S. Ct. 1612 (U.S. 2022).

In his work on tribal constitutions, Anderson (2016) treats blood quantums as independent variables, finding that they predict the presence of a casino on the reservation. While he does not offer an explanation for this result, our framework suggests that blood quantums prevent the dissipation of rents generated by operating an Indian casino, thus increasing the profitability of this enterprise.

We are not the first to systematically study American Indian constitutions. Using a similar approach, Anderson (2016) looked at the historical determinants of constitutional choice, especially the role of the historical centralization of tribal political organization and the decision of the federal government to force separate bands to merge into one political unit during the removal and reservation period, for which he finds mixed evidence.

Voigt (1997, 2011) for a survey of this literature.Fahy (1998) finds evidence broadly consistent with Sass (1991) in the constitutions of local governments in Massachusetts. Leeson (2009) employs a similar framework to study piratical constitutions.

Others have pointed out the detrimental role of federal policies such as removal and the allotment system and the IRA (McChesney, 1990; Anderson & Parker, 2008, 2009; Dippel, 2014; Feir et al., 2019; Leonard et al., 2020; Frye & Parker, 2021) argue that legal institutions and whether a tribe has to independent courts are partially responsible for the variation in economic performance between tribes.

Not generally at least. For an exception, see the discussion of the rise of democracy in Ancient Greece in Fleck & Hanssen (2018).

See Driver (2011) for an overview of the political organization of American Indian peoples in the pre-Columbian period.

For instance, by way of cultural influence but also as an unintended outcome of the process of Indian removal.

The IRA was part of a broader change in the federal government’s agenda towards tribal groups known as the “Indian New Deal.“ Due to their peculiar status, Alaskan, Hawaiian, and Oklahoman native groups were excluded from the IRA. However, Congress promptly passed follow-up legislation to address each of these cases. In the case of Oklahoman Indians, the content of this legislation (the Oklahoman Indian Welfare Act of 1936) was largely analogous to the IRA.

The turn was steeper in rhetoric than in practice. For those tribes that opted into the IRA, the BIA maintained significant oversight over the internal affairs of reservations, ultimately to the detriment of tribes’ long-term economic performance (Frye & Parker, 2021).

Of the 258 tribes that voted on the provisions of IRA, over two-thirds did so in the affirmative; in 77 tribes, a majority rejected the initiative (Haas, 1947, 3). Notably, (Crepelle, 2019, 439) has suggested that the BIA’s administration of the votes on the approval of the IRA and the ratification of the new constitutions was in some respects “illegitimate”.

As Kelly (1975, 299) notes, however, federal interference with tribal political and social life was reined in following the IRA: “Between 1933 and 1945 the excessively authoritarian powers of the Indian Bureau and its employees in the field were curbed substantially.

A draft of this model constitution can be found in Cohen (2006).One hundred and nine tribes were terminated by the federal government during this period (Wilkins, 2007, 120).

See Anderson & Parker (2008) for an evaluation of the consequences of Public Law 280 to American Indian welfare.

For instance, Wilkins (2007, 147-8) discusses the amendment of the Navajo constitution in 1989 to limit the powers of the executive branch.

This is the methodological stance proposed in Buchanan & Tullock (1965) in the context of democratic politics and extended by Grossman & Hart (1988) to constitutional choice in private corporations.

If a production process is characterized by U-shaped average costs, as is the case for grazing, Johnson & Libecap (1980) argue for an alternative solution: Larger-than-optimal individual herds. The latter functioned effectively as entry-deterring excess capacity, discouraging entry and thus limiting rent-dissipation. However, the resulting rents are smaller than if entry could be otherwise restricted.

Blood quantums were commonplace in colonial America and throughout the first two centuries of United States history, particularly concerning the legal status of African Americans (Spruhan, 2006; Bodenhorn & Ruebeck, 2003) provide an economic explanation for the centrality of blood quantums in early American history.

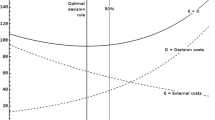

On this issue, see the discussion by Mueller et al., (2003).This effect has been found in a wide array of circumstances. For instance, Sass (1991, 75) finds that “[l]arge cities don’t hold town meetings simply because it would be too expensive.”

Notice that with respect to the US Federal government, one needs to be at least 35 years old to be eligible to the presidency but only 30 to become a Senator and 25 for becoming a Representative. This is exactly what our theory predicts. Senators, serving in a chamber with fewer members, have greater political power and more room to act opportunistically.

For instance, Venetians, being extremely fearful of tyranny, developed the habit of nominating elderly Doges during the Middle Ages and Renaissance (Smith et al., 2021).

Hayek (2011) proposed establishing a legislature with a 45 year old minimum age requirement to make sure representatives have a good reputation.

In Federalist 10, Madison argues that “however small the republic may be, the representatives must be raised to a certain number, in order to guard against the cabals of a few; and that, however large it may be, they must be limited to a certain number, in order to guard against the confusion of a multitude.”

For instance, socialist countries typically have massive legislatures with more than 1,000 members.Such expectations were eminently reasonable. John Collier, the head of the BIA between 1933 and 1945, was explicit in his desire to see the effects of the allotment process fully reversed, including the return of allotted land to tribal common ownership (Kelly, 1975).

Many Indian beneficiaries never gained full (“fee simple”) ownership of their land. While they could use the latter as they pleased, they could not sell it without the approval of the BIA. For a discussion of the allotment system and its consequences, see McChesney (1990) and Leonard et al., (2020).

In collecting this information, we treated amended constitutions as separate observations from the original document.

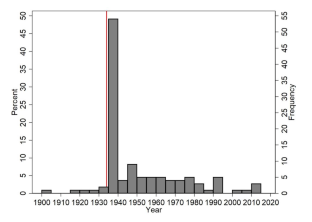

Indeed, reading tribal constitutions, one quickly realizes that the constitutions enacted in the 1930s, ’40s and ’50s are substantially different from those drafted from the 1970s onward. Although the evolution of constitutions through time is itself a question worth investigating, we here restrict our attention to a specific period going from 1934 to 1950.

All of the links are available on http://thememoryhole2.org/blog/tribal-constitutions (Last accessed on 2/19/2022).

It is not clear how widespread blood quantums had been among American Indian tribes before the Indian Reorganization Act, in part due to the fact that most of their constitutions had not been written down. One potential cause behind the popularity of blood quantums in the IRA constitutions is that the BIA encouraged tribes to adopt one (Frye et al., 2020). However, formulation from the “model constitution” made available to American Indian tribes by the BIA reads as follows: “The membership of the [blank] Tribe of Indians shall consist of … All persons of Indian blood whose names appear on the official census rolls of the tribe as of April 1, 1935.“ While there is a reference to “persons of Indian blood,“ there is not one to minimum blood quantums. Moreover, there is some evidence that the idea of restricting membership on the basis of blood was not alien to American Indian polities. Cohen (2006) discusses several instances of tribal constitutions from the early decades of the twentieth century that already contain blood quantums. Moreover, the oldest written American Indian constitution, the Great Law of Peace of the Iroquois Nations, already stipulated membership restrictions on the basis of blood: non-Iroquois were excluded from democratic deliberation on the basis that “[aliens] have nothing by blood to make claim to a vote” (Wilkins, 2009, p. 30).

We also used the “hunspell” package in R to check spelling mistakes and correct them.We used the population figure from that document because it could easily be cross-referenced with the population figures given in Haas (1947).

We use data from 1926 because it enables us to control for tribal characteristics before the IRA.Inequality in landholding might also have influenced tribes’ constitutional choice. For instance, wealthier residents might have a greater interest in adopting representative over direct democracy or lobby for stronger protections for the rights of allottees. Unfortunately. we do not have the data to control for these potential effects. Thankfully, the allotment system was meant to allocate land equally across Indian residents and restricted sales to third parties, which would have limited the ability to accumulate large holdings, making inequality of this sort less of a concern.

In appendix E, we show that our results are robust to changing our population threshold by including 28 constitutions from smaller tribes.

Throughout the rest of the paper, we report our results with standard errors doubly clustered at the BIA region and year levels (in parenthesis).

One anonymous reviewer suggested the possibility that more cooperative tribes might be both more productive (which could increase the share of the value of the land held in common) and less likely to adopt strict quantums. In that case, our inability to control for this variable would negatively bias our coefficient on Tribal Land Value Share. If so, our estimates could be considered conservative.

Related to this result, Frye et al., (2020) find economic growth (in some instances generated by the opening of casinos on reservations) led to higher levels of conflict about blood quantum-based membership requirements when tribes are more ethnically diverse.

Our “Mixing,” “Speaks English,” and “Citizen Clothing” variables are also proxies for a tribe’s length of exposure to Europeans. Notice that the effect of the length of exposure to Europeans on blood quantum is unclear as it likely impacts human capital, how embedded a tribe is in the broader society, as well as many other variables. The type of exposure to Europeans–violent or peaceful–may also matter. Here too our cultural variables are useful proxies as tribes facing violent interactions with Europeans are probably more likely to maintain sharply separate cultural traits. For some examples of conflict or relatively peaceful behavior between Indians and settlers, see Candela & Geloso (2021) and Geloso & Rouanet (2020).

To verify the validity of our econometric results, we operate a number of robustness checks in the appendix. First, we use data from Wilson (1935) which measures the portion of reservations covered by tribal land in 1934 (as opposed to its $ value in 1926). The results are included in Appendix B. Second, a few constitutions in our sample, despite being very similar to the other constitutions in style, did not have an Indian Reorganization Act or Oklahoma Welfare Act status. We control for this in Appendix C. Third, we check if our results are robust to changes in our chosen population threshold (Appendix E). Finally, because of the small size of our sample, we check if our results are robust to the exclusion of potential outliers as well as to changes in our chosen date for the end of the sample (1951). For each selected sample with an end date ranging from 1941 to 1951, we follow a “leave one observation out” process by rerunning our main regressions. The results of all these regressions are reported in Appendix F.

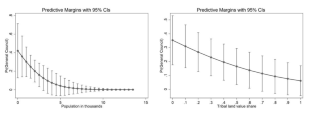

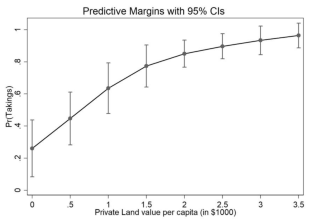

We do not add decade or year fixed as it would drop a substantial number of observations.The predicted probabilities in Fig. 2 have been calculated by assuming that all other independent variables are at their average level.

In a separate set of regressions, we also investigated the determinants of the size of the tribal council, but our results are not statistically significant. This is consistent with Stigler’s (1976, 19) observation that “legislatures […] are remarkably similar and stable in size.” In other words, there may too little variation in the optimal size of legislatures, and our sample may be too small, to identify the effect of the value of tribal assets on the size of tribal councils. To economize on space, we do not report our regressions with the size of the tribal council in the body of the paper. We report those results in Appendix D.

Some tribes also included unique restrictions on voting such as living requirements, perhaps to prevent members living off reservation from taking advantage of the resources held in common. Other considerations, such as avoiding political polarization based on familial allegiances, may have played a role as well. For instance, the 1947 Constitution of the Isleta Pueblo tribe (New Mexico) sets voting age at 21 years old and requires that the individual live independently of his or her parents.

These age requirements may seem fairly low, yet we should keep in mind that American Indian tribes’ demographics was very young in the 1930s. 77% of tribes from our sample enacting a constitution from 1934 to 1950 had minors composing more than 50% of their population in 1926 and 23% more than 60%. Still in 1965, President Lyndon Johnson mentioned in his Special Message to the Congress on the Problems of the American Indian that “‘The average age of death of an American Indian today is 44 years; for all other Americans, it is 65.”

Regressions in Table 3, columns 7 and 8 remain statistically significant at the 5% level when removing “Recall” for the “Tribal land value share” variable. The p-value for that variable in column 6 increases to 0.106.

For instance, the 1935 constitution of the Blackfeet tribe in Montana stipulates that “It is recognized that under existing law [allotted] lands may be condemned for public purposes, such as roads, public buildings, or other public improvements, upon payment of adequate compensation.” (Art.VII, Sect. 1). In some rare occasions, tribes went further by inscribing the right to private property into the constitution. In the 1960s the Yankton Sioux in South Dakota went so far as to include that “all operation under this Constitution shall be free from any system of collectivism/socialism under any and all circumstances” (Art.IX, Sect. 1) and recognized “the private enterprise system.” (Art. IX, Sect. 2).

Table 4 does not include controls for cultural characteristics since doing so does not affect the overall results.

Haas (1947, 7) notes that at the time the IRA was passed, “Fantastic rumors were spread, such as: the bill was designed to deprive the Indians of the interests in their lands, to take away their allotments and communize them […].”

References to inheritance include the following words: heir, heirs, inherit, inheritance, inheritances, inherited, inheriting, inherits. References to allotment include the following words: allotment, allotments, allotted, allotting.

See Leonard et al., (2020) for a study about the negative effects of the high fractionalization of land due to the allotment system.

We used the following roots: “cultur–,”tradition–” and “custom–.”